title

Les Mots et les Choses 1.1 – 1.2

subtitle

Die Ordnung der Dinge

year

2008

material

C-print . laser engraved . lasercut

edition

1+1ae

seize cm

1.1 120x180

1.2 40x120

. .

. .

exhibitions

2004 06 05 . Crane neck and Gold crepine . Vienna . Khm . Wagenburg >

usage

cc by-nc-sa

info

Inrtoduction from the exhibition Catalogue . Crane neck and gold crepine . text © Elisabetta Brescian

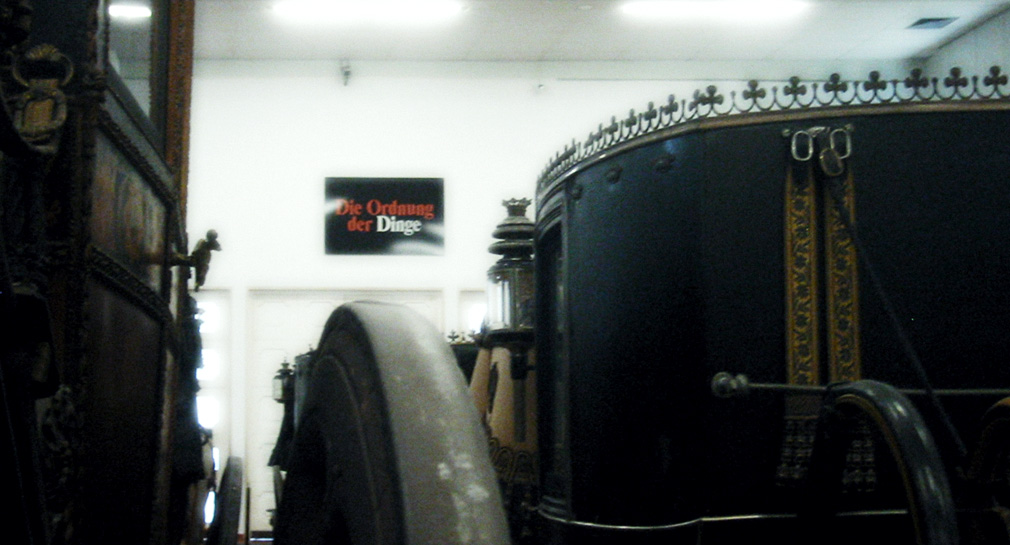

Erica Ratvay photographs the German title in serif typography 'Die Ordnung der Dinge' after Michel Foucault (Les mots et les choses, Paris 1966) and cuts out the word Dinge.

Besides the black cover and the orange-coloured letters, not only can the light base of the photographic paper be seen but also the texture of these three components from which a three-dimensionality is produced.

The cut out letters are then arranged above each other, outlined and then as a separate photo work confront the first photograph.

It is kept uniformly in orange as a reference to the colour originally used for the lettering on the book cover (Suhrkamp).

The resulting empty space in the one and the overlapping of the individual elements in the other work complement one another to become a kind of reusable stencil for the combination of things in exhibitions.

The content of the book becomes the departure point for the intention to demonstrate to what extent methodical collecting can be understood as the acquisition of knowledge or whether it is not rather a question of a general necessary structuring.

Through the title of the work Les mots et les choses, the principle of de- and recontextualisation is consistently continued.

In that the subject transforms into object and is taken up in the, at first, reference-free environment, it leaves a gap in the old order and in its new surroundings supplements the structure which then gradually forms.

exhibition

Les Mots et les Choses1.1 – 1.2

2004 06 05 . Crane neck and Gold crepine .Vienna . Khm . Wagenburg

www.khm.at >

www.khm.at >

append

Interview from the exhibition Catalogue . Crane neck and Gold crepine . interview © Elisabetha Bresciani

ELISABETHA BRESCANI “You’re a trained architect and therefore you have a pronounced feeling for spatial situations.

What was the stimulus for you to add a separate artwork to the objects in the exhibition space of the Wagenburg, where the first impulse far more seems to be to take something away, very simply, in order to create more space.

So what does space mean for you in connection with a collection?”

ERICA RATVAY “It is about ‘creating’ space and not about ‘making’ space; so I am concerned with the ways in which things are arranged.

I want to create a space with limits, to organise it and structure it.

An empty space does not exist – certainly not at all for our perception.

It takes on its identity only through the way in which things organise themselves in space.

In a collection this organisation is desired, because one wants to show something particular.

But in a completely everyday space we must often first ‘recognise’ such organisation, that’s to say, we must project it into the space (otherwise we couldn’t orientate ourselves).

When you go into the Wagenburg exhibition collection, in a certain way you enter a closed world which functions within itself.

It is a clearly arranged, rectangular room in which the objects are carefully lined up together.

The collection can always only show a fraction of its stock, a selection according to a certain ordering system.

Above this is the system of archiving which also contains information about the things which is not shown but stored in the depot.

My work interprets the collection as selected order and our view of the world as selected order.

It plays through this order another time.

It works like a stencil, a net that filters and sorts and names similarities – and thereby creates a system in which we then move.

It is the photo of the cover of the German version of The Order of Things by Michel Foucault (Die Ordnung der Dinge: in French Les mots et les choses, literally: Words and Things, Edition Gallimard 1966).

This book is concerned with the structuring of knowledge.

We order and collect because this structure exists which conveys certain values, from which a Wagenburg also derives its justification to exist.”

EB “You now mainly occupy yourself with photography and graphic arts.

Much of it is to do with linking individual pictures on a computer.

Is this principle a starting point for you for your engagement with the theme of collecting and sorting, which appears to interest you not only in relation to this exhibition, but which often returns as a motif in your artistic work?”

ER “In the digital field collecting and sorting works in a different way: the objects take up no space, they don’t really exist next to each other; a component must always be clearly identified because at the very beginning you don’t see the thing itself but only a name.

But there’s also no original or any difference between copy and original.

In this respect the idea of collecting must also be valued differently to when it is about physical things.

The order is very strict on the one hand but on the other very flexible, because more systems can be produced next to one another through references.”

EB “So collecting is to be understood analogously to the structuring of everyday life?

And what role does the principle of the series or the cycle play in your works?”

ER “‘Series’ and ‘cycle’ – these words stand opposite each other like ‘collecting’ and ‘everyday life.’

Collecting has to do with things being side by side whereas everyday life has to do with a temporal return.

Collecting refers to the serial, everyday life in contrast to the cyclical, in so far as the same activities are ritually repeated again and again: you can’t make a collection out of that.

the same – the same (Dasselbe – das Gleiche)

collecting – structuring of everyday life

series – cycle

However, in collecting one takes something from everyday life, one transfers something from the cyclic to the serial, one puts things next to each other, makes them comparable and takes them out of their temporal context.

It’s a question of the order which is explicit in the collection and is always first produced in everyday life: according to Wittgenstein there is no order a priori.

Through ordering, we attempt to come to an understanding of our world.

Only in this way is it possible to pass on knowledge and to write history.

By leaving things out, summarising and simplifying we produce the image of a truth – a counterpart.

If one makes more things that are similar, and so are put into a series, then they are not only connected because of this, but certain themes, differences or characteristics will also be more easily recognisable.

One is always looking for an order and logic that one can add to what is observed.”

What was the stimulus for you to add a separate artwork to the objects in the exhibition space of the Wagenburg, where the first impulse far more seems to be to take something away, very simply, in order to create more space.

So what does space mean for you in connection with a collection?”

ERICA RATVAY “It is about ‘creating’ space and not about ‘making’ space; so I am concerned with the ways in which things are arranged.

I want to create a space with limits, to organise it and structure it.

An empty space does not exist – certainly not at all for our perception.

It takes on its identity only through the way in which things organise themselves in space.

In a collection this organisation is desired, because one wants to show something particular.

But in a completely everyday space we must often first ‘recognise’ such organisation, that’s to say, we must project it into the space (otherwise we couldn’t orientate ourselves).

When you go into the Wagenburg exhibition collection, in a certain way you enter a closed world which functions within itself.

It is a clearly arranged, rectangular room in which the objects are carefully lined up together.

The collection can always only show a fraction of its stock, a selection according to a certain ordering system.

Above this is the system of archiving which also contains information about the things which is not shown but stored in the depot.

My work interprets the collection as selected order and our view of the world as selected order.

It plays through this order another time.

It works like a stencil, a net that filters and sorts and names similarities – and thereby creates a system in which we then move.

It is the photo of the cover of the German version of The Order of Things by Michel Foucault (Die Ordnung der Dinge: in French Les mots et les choses, literally: Words and Things, Edition Gallimard 1966).

This book is concerned with the structuring of knowledge.

We order and collect because this structure exists which conveys certain values, from which a Wagenburg also derives its justification to exist.”

EB “You now mainly occupy yourself with photography and graphic arts.

Much of it is to do with linking individual pictures on a computer.

Is this principle a starting point for you for your engagement with the theme of collecting and sorting, which appears to interest you not only in relation to this exhibition, but which often returns as a motif in your artistic work?”

ER “In the digital field collecting and sorting works in a different way: the objects take up no space, they don’t really exist next to each other; a component must always be clearly identified because at the very beginning you don’t see the thing itself but only a name.

But there’s also no original or any difference between copy and original.

In this respect the idea of collecting must also be valued differently to when it is about physical things.

The order is very strict on the one hand but on the other very flexible, because more systems can be produced next to one another through references.”

EB “So collecting is to be understood analogously to the structuring of everyday life?

And what role does the principle of the series or the cycle play in your works?”

ER “‘Series’ and ‘cycle’ – these words stand opposite each other like ‘collecting’ and ‘everyday life.’

Collecting has to do with things being side by side whereas everyday life has to do with a temporal return.

Collecting refers to the serial, everyday life in contrast to the cyclical, in so far as the same activities are ritually repeated again and again: you can’t make a collection out of that.

the same – the same (Dasselbe – das Gleiche)

collecting – structuring of everyday life

series – cycle

However, in collecting one takes something from everyday life, one transfers something from the cyclic to the serial, one puts things next to each other, makes them comparable and takes them out of their temporal context.

It’s a question of the order which is explicit in the collection and is always first produced in everyday life: according to Wittgenstein there is no order a priori.

Through ordering, we attempt to come to an understanding of our world.

Only in this way is it possible to pass on knowledge and to write history.

By leaving things out, summarising and simplifying we produce the image of a truth – a counterpart.

If one makes more things that are similar, and so are put into a series, then they are not only connected because of this, but certain themes, differences or characteristics will also be more easily recognisable.

One is always looking for an order and logic that one can add to what is observed.”

October 25th, 2021